- religion

- SEE MORE

- classical

- general

- talk

- News

- Family

- Bürgerfunk

- pop

- Islam

- soul

- jazz

- Comedy

- humor

- wissenschaft

- opera

- baroque

- gesellschaft

- theater

- Local

- alternative

- electro

- rock

- rap

- lifestyle

- Music

- como

- RNE

- ballads

- greek

- Buddhism

- deportes

- christian

- Technology

- piano

- djs

- Dance

- dutch

- flamenco

- social

- hope

- christian rock

- academia

- afrique

- Business

- musique

- ελληνική-μουσική

- World radio

- Zarzuela

- travel

- World

- NFL

- media

- Art

- public

- Sports

- Gospel

- st.

- baptist

- Leisure

- Kids & Family

- musical

- club

- Culture

- Health & Fitness

- True Crime

- Fiction

- children

- Society & Culture

- TV & Film

- gold

- kunst

- música

- gay

- Natural

- a

- francais

- bach

- economics

- kultur

- evangelical

- tech

- Opinion

- Government

- gaming

- College

- technik

- History

- Jesus

- Health

- movies

- radio

- services

- Church

- podcast

- Education

- international

- Transportation

- Other

- kids

- podcasts

- philadelphia

- Noticias

- love

- sport

- Salud

- film

- and

- 4chan

- Disco

- Stories

- fashion

- Arts

- interviews

- hardstyle

- entertainment

- humour

- medieval

- literature

- alma

- Cultura

- video

- TV

- Science

- en

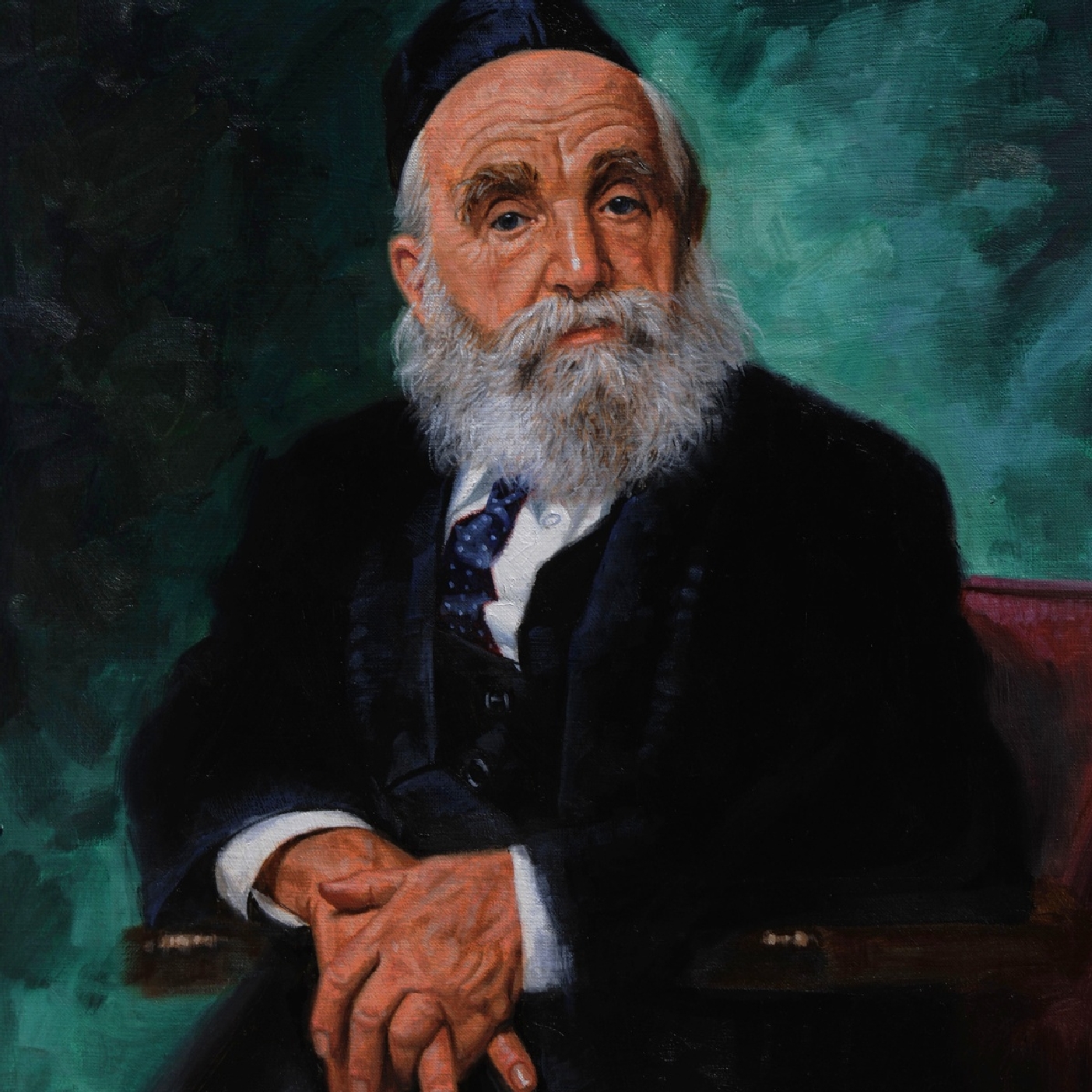

Rav Moshe-The Art of Psak with Rabbi Aryeh Klapper-Episode 1-The Limits of Empirical Research-Is Freeing an Agunah a Leniency or a Stringency?

Practical Halakhah exists in constant dialogue with the world around it. Competent poskim know and respond to the social, political, and economic realities of their communities. In turn, halakhah shapes those realities in important ways. Consider for example the effect of capitalism on the laws of interest, and the effect of halakhah on the price of ungrafted citrons.

\nIgrot Mosheh EH 1:49 was written when Rav Moshe Feinstein was living in Luban, Belarus. According to the biography printed at the start of Igrot Mosheh vol. 8, most of Rav Moshe\u2019s teshuvot written in that period were lost in transit. The ones that survive often establish themes that recur in his halakhic decisions. In general, while Rav Moshe\u2019s specific halakhic positions sometimes shifted over time, his underlying commitments were rock-solid. One of those commitments was to freeing agunot, and more, to an expansive notion of what constitutes a situation of iggun.\xa0\xa0

\nBelarus had joined the USSR in 1922, and Stalin had come to power in 1924. The combination of ideological opposition to religion and totalitarianism changed the reality of agunah cases in three ways. First, many women had a real option of leaving the religious community if the rabbis refused them permission to remarry. Second, even women who stayed within the community might see halakhah on this issue as an obstacle course rather than as a substantive moral guide. Third, husbands might very well be \u201cdisappeared\u201d forever without notice and without record. Each of these factors potentially altered the classical calculus of credibility.\xa0

\nMishnah Yebamot 15:1 states that if a couple goes abroad, and the woman returns alone claiming to be a widow, she is believed, even if her ground for the claim is hearsay. Ordinarily, two valid direct witnesses are necessary to undo a presumption of marriage. The Talmud offers a complex explanation for why the standards of evidence are relaxed here. There is a stick: if a court allows the remarriage and the husband turns up alive, she is forbidden to both men, and her children from the remarriage are now considered mamzerim.\xa0 There is a motive: the Rabbis were lenient in order to free women from being agunot. And there is a rationale, framed as a chazakah or legal presumption: women investigate comprehensively before they remarry.

\nRav Moshe\u2019s interlocutor questions whether the chazakah is still applicable. He notes that in the Talmud, a woman is believed if she claims in her presumptive husband\u2019s presence that he has divorced her. The ground for believing her is a chazakah attributed to Rav Hamnuna that \u201cA woman is not brazen in the presence of her husband\u201d. But RAMO EH 17:2 codifies the position that because of societal changes, this chazakah no longer generates the credibility necessary to allow remarriage. Perhaps the same is true for the chazakah that woman investigate comprehensively before remarrying?

\nRav Moshe responds with an emphatic no. The changes that led RAMO to sideline Rav Hamnuna\u2019s chazakah regarding divorce have no necessary implications for the chazakah regarding death. Rav Moshe ignores entirely, and I suggest deliberately, the question of whether changes specific to his own time and place have weakened the latter chazakah. Everything he says could have been written identically in the late 16th century.

\nTwo halakhic issues remain, however.

\nThe first is that the Mishnah says that the widow is believed only if \u201cthere is peace in the world and peace among them\u201d. If there is war, then perhaps the husband is alive and prevented from returning or communicating. If there was marital strife, then perhaps the husband is maliciously staying out of contact precisely to make his wife an agunah. Rav Moshe notes that even by the woman\u2019s account, the husband had been completely out of touch for twenty years before his death. That seems to show clearly that he was in fact willing and maybe eager to leave her an agunah, so why is she believed?

\nHe offers three responses.

\nThe first is entirely technical. Talmud Yebamot 116a limits \u201clack of peace between them\u201d to the extreme case in which the wife has previously made a false claim of divorce. RAMO EH 17:48 cites a position that adds the case of a husband who apostasized. Rav Moshe argues that RAMO does not intend to broaden the category to cases like those two cases, but only to add that one case. He contends that this is a better reading of RAMO\u2019s source in Shiltei Gibborim. (I am not sure why.)

\nRav Moshe\u2019s second response is that in this case, there are witnesses that the woman behaved as a widow the moment she reported the husband\u2019s death. He contends that this enhances her credibility. (I am not sure why.)

\nThe third response is that even the extension to apostasy is controversial.

\nRav Moshe does not address the question whether the gulag might play the same role as \u201clack of peace in the world\u201d.

\nOverall, Rav Moshe\u2019s responses seem weak if his goal is to convince us that the woman is obviously being truthful. However, they make a great deal of sense in light of Maharik #72.

\nMaharik notes that Mishnah Yebamot 15:2 frames the decision to relax the standards of evidence as resulting from a specific case in which a beit din investigated a woman\u2019s claim to be widowed and it proved true. Tosafot Yebamot 116b comment that \u201cbecause they saw that there would be many agunot if they did not believe her\u201d. Maharik explains that the specific case taught the Rabbis that even women who told the truth would often be unable to find sufficient formal evidence. The Rabbis knew that some women would falsely claim to be widows; it would be ridiculous to conclude from one case that all women always told the truth in such situations. But they created the legal presumption anyway, because the consequences of the higher standard were unbearable.

\nRav Moshe does essentially the same thing. He presumably knows that the situation in the USSR made false claims more likely, but it also made more true claims impossible to prove. The balance of those changes meant that the rule should be left intact.

\nHowever, a compromise is available. Rav Moshe has the option of saying that the rabbi should at least make a good faith effort to verify the woman\u2019s claim before permitting her to remarry. Pitchei Teshuvah 17:158 cited Radbaz as saying that in some cases where an investigation can be easily done, it must be done.

\nRav Moshe declines the compromise, on two grounds. First, he asserts that Radbaz required this only in cases where a woman was reputed to be licentious, and he sees no grounds for making this a general rule. (It seems likely that Rav Moshe did not see the original of Shu\u201dt Radbaz 3:542, which strongly confirms his position. Radbaz seems to be dealing with a case in which a woman had made previous false claims of widowhood.) Second, Rav Moshe writes that since there is a man prepared to marry the widow in his case, and that man may not be willing to wait around while the rabbi investigates \u2013 the case is one of iggun gamur, just as if the woman were being prevented from marrying at all. (It\u2019s not clear whether Rav Mosheh would have the same objection if the woman did not have a proposal in hand.)

\nI derive three principles from this teshuvah of Rav Moshe.

\n1) While chazakot are influenced by social changes, there is no straight line from a change in circumstances to a change in law. The legal presumptions that Chazal created via chazakot resulted from an interplay between their evaluation of reality and their sense of what halakhic outcomes were necessary or desirable.

\n2) Decisions in agunah cases are not properly classified as chumrot or kullot. Preventing a woman from remarrying is a wrong comparable to the stringency of allowing a woman to commit adultery. I don\u2019t mean that 50/50 cases should be decided by a coinflip, or even necessarily that one can permit remarriage when the odds are less than 999,999,999 to 1. What I mean is that Chazal set up a very precise balance, and that any deviation from that balance, either way, is equally problematic.

\n3) For agunot, justice delayed is justice denied.

\n\n\n\n\n\nRabbi Aryeh Klapper is Dean of the Center for Modern Torah Leadership, Rosh Beit Midrash of its Summer Beit Midrash Program and a member of the Boston Beit Din.

\n\nRabbi Klapper is a widely published author in prestigious Hebrew and English journals. He is frequently consulted on issues of Jewish law from representatives of all streams of Judaism and responds from an explicit and uncompromised Orthodox stance.

\n\nThe Yeshiva of Newark @IDT is proud to partner with Rabbi Klapper to help spread his scholarly thoughtful ideas and Halachic insight to as wide an audience as possible .

\n\nPlease visit

\n\nhttp://www.torahleadership.org/

\n\nfor many more articles and audio classes from Rav Klapper and to find out about his Summer programs as well as Rabbi Klapper's own podcast site

\n\nhttps://anchor.fm/aryeh-klapper.

\n\nPlease leave us a review or email us at ravkiv@gmail.com This podcast is powered by Jewish Podcasts. Start your own podcast today and share your content with the world. Click here to get started.

\n This podcast has been graciously sponsored by JewishPodcasts.fm. There is much overhead to maintain this service so please help us continue our goal of helping Jewish lecturers become podcasters and support us with a donation: https://thechesedfund.com/jewishpodcasts/donate