- Other

- SEE MORE

- classical

- general

- talk

- News

- Family

- Bürgerfunk

- pop

- Islam

- soul

- jazz

- Comedy

- humor

- wissenschaft

- opera

- baroque

- gesellschaft

- theater

- Local

- alternative

- electro

- rock

- rap

- lifestyle

- Music

- como

- RNE

- ballads

- greek

- Buddhism

- deportes

- christian

- Technology

- piano

- djs

- Dance

- dutch

- flamenco

- social

- hope

- christian rock

- academia

- afrique

- Business

- musique

- ελληνική-μουσική

- religion

- World radio

- Zarzuela

- travel

- World

- NFL

- media

- Art

- public

- Sports

- Gospel

- st.

- baptist

- Leisure

- Kids & Family

- musical

- club

- Culture

- Health & Fitness

- True Crime

- Fiction

- children

- Society & Culture

- TV & Film

- gold

- kunst

- música

- gay

- Natural

- a

- francais

- bach

- economics

- kultur

- evangelical

- tech

- Opinion

- Government

- gaming

- College

- technik

- History

- Jesus

- Health

- movies

- radio

- services

- Church

- podcast

- Education

- international

- Transportation

- kids

- podcasts

- philadelphia

- Noticias

- love

- sport

- Salud

- film

- and

- 4chan

- Disco

- Stories

- fashion

- Arts

- interviews

- hardstyle

- entertainment

- humour

- medieval

- literature

- alma

- Cultura

- video

- TV

- Science

- en

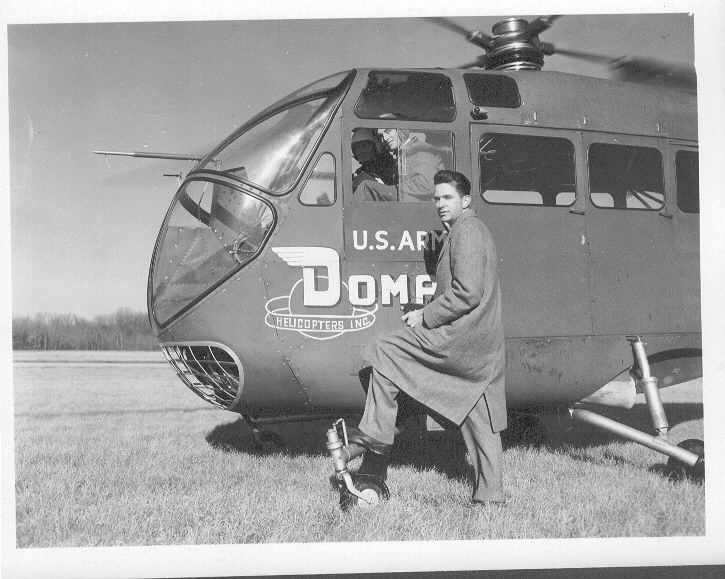

The Last Helicopter Pioneer Innovation Insights from my Father, Glidden S. Doman

b'

Barefoot Innovation has been in hiatus in recent weeks because my father passed away. I was in San Francisco and got a call saying he was suddenly ill and might not live through the day. I rushed for a redeye and flew all night home to Boston, where my son Matt met me and we drove to Harford in the wee hours. My brother and sister had rushed to our Dad too, and he had held on. In fact he began to do better, regaling us with stories in the ICU, bringing his sharp engineering mind to analyzing his medical situation, and enjoying us singing to him (we\\u2019re a singing family). We had hopes he would recover, but a few days later, he worsened and ultimately did not pull through.

He was 95 years old. His name was Glidden Sweet Doman. And he was a remarkable innovator. He\\u2019s being widely remembered as the last of the great helicopter pioneers, and he was also an important inventor in wind energy. Those two industries share the same technology \\u2013 the wickedly complex science of rotor dynamics.

This very special episode of Barefoot Innovation is a conversation I recorded with him last Thanksgiving but had not yet posted. I got the idea of doing this podcast after watching a video of a talk\\xa0he\\u2019d recently given at the New England Air Museum, which has two of his Doman Helicopters on permanent display. Listening to his lecture, I kept noticing parallels with the themes we discuss on Barefoot Innovation. It occurred to me that it would be fun to do a show inviting insights from someone who, nearly a century ago, began innovating in a field that\\u2019s very different from finance, but that was being similarly transformed by new, fast-changing technology.

Glid Doman was born in the village of Elbridge, New York, in 1921. His father, Albert Doman, brought electricity to that part of the state in 1890 (you can still see historic sites related to it), and was an inventor of the electric starter and electric windshield wiper. My Dad\\u2019s uncle, Lewis Doman, invented the player piano. His half-brother Carl Doman pioneered both aircraft and automobile engines and became a senior executive at Ford. His half-sister Ruth Chamberlain was the first woman architect in the region. My family is loaded with the genes for invention and entrepreneurship.

For my Dad as a boy, the most exciting field of invention was aviation. Airplanes were barnstorming farm fields. Airlines did not yet exist. And my Dad, who avidly read Popular Mechanics, built an airplane in his back yard (you\\u2019ll hear in the podcast whether he ever made it fly).

Aviation was the new technology then, the way digitization and mobile phones and blockchains are the tech frontiers today -- or genetics or robotics or 3D printing. Aviation was full of novel engineering challenges that were not yet understood. Flight was also inspiring bold predictions about how our lives were going to change, some of which were hilariously wrong \\u2013 a good lesson for people like me who like to try to forecast tech impacts. For instance, in clearing out our parents\\u2019 attic in recent days, my siblings and I found a magazine cover story advising on women\\u2019s fashion for the coming trend of traveling by helicopter.

This little podcast touches only a tiny fragment of what made my Dad fascinating, and has nothing on his great life partner, our late mother, Joan Hamilton Doman. They met because she was the only woman in the 50-person University of Michigan flying club in World War II \\u2013 and she was its top pilot. They had an amazing six decades or so, built around family and his work. He knew all the aviation greats from Igor Sikorsky to Charles Lindberg. He was featured on aviation magazine covers and traveled throughout the world. He was enlisted by NASA\\u2019s Jet Propulsion Lab to help design a \\u201cspace sail\\u201d to rendezvous with Haley\\u2019s Comet (ultimately not deployed). He\\u2019s been honored by his alma mater, the University of Michigan aeronautical engineering school. And when his helicopter company didn\\u2019t reach scale, he pivoted to wind energy and invented a superior rotor design for wind turbines, using the same insights he\\u2019d developed working with helicopters. He led the design of two colossal experimental turbines funded by the Departments of Energy and Interior and installed in Wyoming. When he \\u201cretired\\u201d at age 65, he and my mother moved to Rome where he led international engineering teams in designing huge turbines in Europe.

And then, in his 80\\u2019s, he started a new wind energy venture of his own.\\xa0 Right up to his death, he continued to be engaged with an affiliated firm, Seawind Technology, which is actively working to deploy his \\u201cGamma\\u201d rotor designs on offshore wind turbines in Europe and other parts of the world.

Decades before computers could model the movements of rotor blades, my Dad used a combination of intuition, math, physics and relentless measurement to understand, correctly, the movement of spinning blades. For both helicopters and wind turbines, my Dad created massively simplified rotor designs and drastically reduced the stress on the blades as they rotate. This captures huge efficiency gains and virtually eliminates blade failure, the bane of most rotor systems. As he explains in our talk, one key to this was to realize that the commonly-used three-bladed rotor design is inherently unstable.\\xa0 Wind turbines, he argued, should have two blades and helicopters \\u2013 because they have to fly forward \\u2013 need four.

Our conversation elicited a lot of my Dad\\u2019s thoughts about how to work with young, little-understood technology, as both an engineer and entrepreneur. While we didn\\u2019t cover all the ground I\\u2019d hoped to, you\\u2019ll hear him imparting Lean Startup-type wisdom. As a young engineer, for instance, he used a jackknife to cut open the balsa wood of a Sikorsky rotor blade to install measurement gauges on it and figure out what it was doing. He bought a postwar helicopter body for a dollar. He got hold of a Chevrolet clutch to use in his helicopter engine. His team invented do-it-yourself wind tunnels. It\\u2019s an MVP approach \\u2013 a minimum viable product \\u2013 in which they methodically identified, isolated, and intensively tested issues and reaped what today we call \\u201crapid learning\\u201d and \\u201cfail-fast\\u201d lessons. As they figured out answers, they quickly pivoted, trying to succeed in an industry where, unlike today\\u2019s fintech, entrepreneurs needed huge amounts of capital. (In our recording, he talks about how easily his enterprise raised money, but that pattern did not hold over the decades.)

Our conversation only touches on a few of these lessons (and nothing about the wind business), but shining through it is his defining trait, the one that made him most successful, which was unbounded and insatiable curiosity.

Mainly, this episode shares his secret to being an innovator \\u2013 and to having a wonderful career. His advice:\\xa0 find organizations that have a lot of interesting problems, and go there and figure out how to solve them.

For those intrigued with the technology history of the twentieth century, I\\u2019m attaching early chapters of a biography that my brother, Steve Doman \\u2013 also an aeronautical engineer -- is writing about our father\\u2019s journey. Here, also, is an overview and short video on Doman Helicopters\\xa0created by my sister, Terry Gibbon (she too is an entrepreneur, with her own video company).\\xa0 And here is a short video of one of the wind turbines.

To prepare this episode, I re-listened to the recording just a few weeks after his passing. One thing I notice is that, as we had this conversation after our Thanksgiving dinner last fall, my Dad\\u2019s comments kept making me laugh. Whenever he said goodbye to people, he always added the advice, \\u201ckeep smiling.\\u201d\\xa0 Words to live by.

Let me share two updates about me and the show.

First, I\\u2019ve become involved in a very significant project aimed at helping prepare our U.S. financial regulatory framework for the challenges raised by innovation. I\\u2019m going to stay in my Harvard fellowship for a second year, still writing my book on innovation and regulation, but will also be devoting much of my time to this initiative, which I\\u2019ll tell you more about as it develops. One result of the new project is that I\\u2019ve decided to suspend the Regulation Innovation video series we launched earlier this year. I expect to reactivate it when I have time to create the videos.\\xa0 Meanwhile, they are still available, still for free, at www.RegulationInnovation.com. Please do check them out. As I said when we started the series, I think the articles that accompany these videos might be the most important writing I\\u2019ve ever done.

Second, we will soon be back from the Barefoot Innovation hiatus, and what a line up we have!\\xa0 We\\u2019ll have CFPB Director Richard Cordray; Digital Asset Holdings\\u2019 Blythe Masters; National Consumer Law Center\\u2019s Lauren Saunders; the prize-winning founders of Bee, Vinay Patel and Max Gasner; Harvard professor and behavioral economics scholar Brigitte Madrian; Funding Circle\\u2019s U.S. CEO Sam Hodges; QED Investors co-founder and venture capital wise man Caribou Honig, and the chief compliance officers of both Citi and Wells Fargo, Kathryn Reimann and Yvette Hollingsworth Clark, together.\\xa0 And those are the ones we\\u2019ve already recorded! We have many more exciting people in the scheduling queue. This is why we ask you to send in \\u201ca buck a show\\u201d \\u2013 the show has turned into a major enterprise, just because we have so many fascinating people to talk with.

We\\u2019ll try to speed up production as best we can, I\\u2019ll look forward to your continued feedback.

Meanwhile, keep smiling.\\xa0 Jo Ann

Click below to donate your "buck a show" to keep Barefoot Innovation going and growing.

Support the Podcast'