752: 3/4 Our Lives, Our Fortunes and Our Sacred Honor: The Forging of American Independence, 1774-1776, by Richard R. Beeman

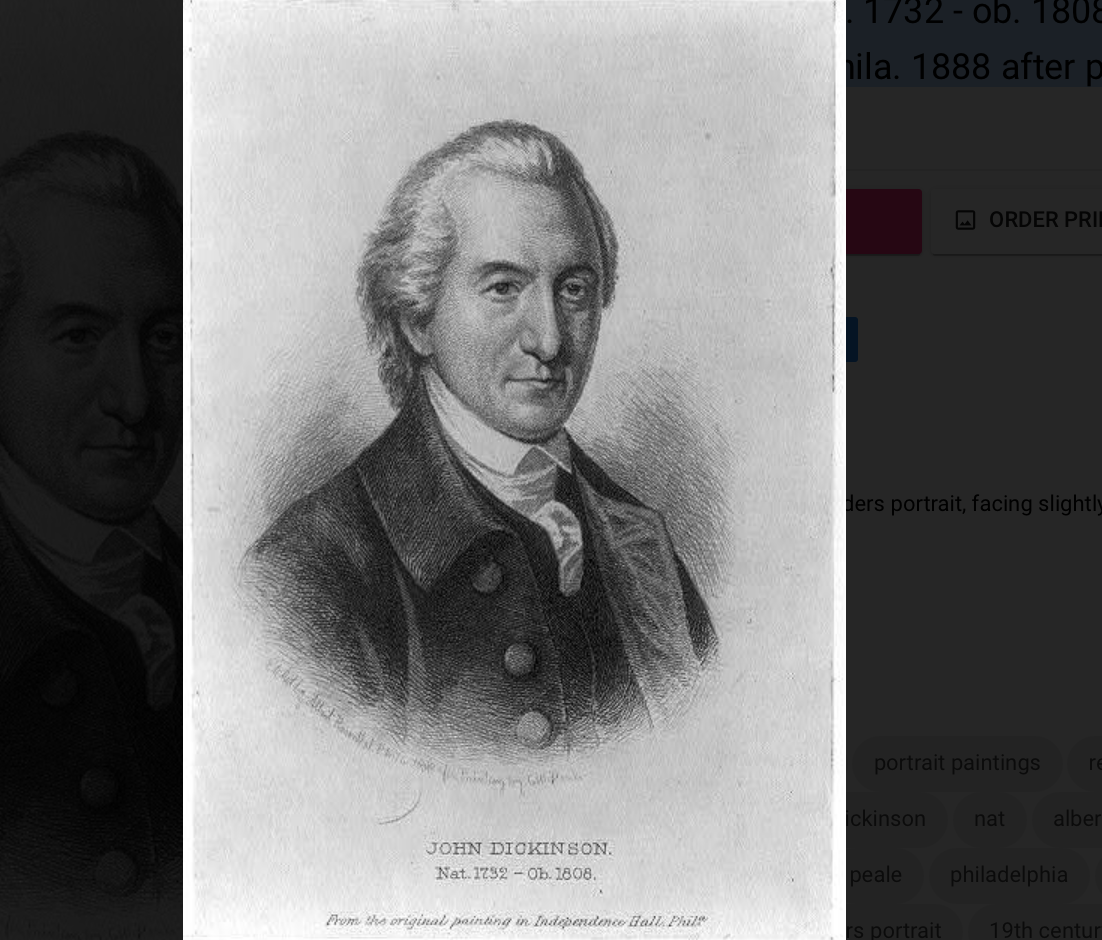

Image: John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, author of Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, challenged the right of Parliament to tax the colonies and had a reputation as a bold defender of American liberties. Etched by Albert Rosenthal, Phila. 1888,after a painting by C. W. Peale. Our Lives, Our Fortunes and Our Sacred Honor: The Forging of American Independence, 1774-1776, by Richard R. Beeman (https://www.amazon.com/Richard-R-Beeman/e/B001H9XBWC/ref=dp_byline_cont_book_1) The Continental Congress first met in September of 1774 in what John Adams described as "a gathering of strangers." It would be almost two years before Thomas Jefferson wrote the last sentence of the Declaration of Independence. "And for the support of this declaration," it reads, "we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor." Here is the inspiration for the title of Richard R. Beeman's new work, which explores how residents of the thirteen distinct colonies, all of whom looked more toward Britain than to one another and at first had no sense of themselves as Americans, became one. He traces the processes by which their chosen legislative body of representatives gained enough cohesion to declare independence. The actions of the Continental Congress, however, were made possible only by the people who composed it. Beeman brings to life this group of politically diverse characters, who fought fiercely among themselves until they agreed to fight together for a common cause. Beeman first outlines how relations between Britain and the American colonies shifted as a result of the Seven Years' War, as a decade of British attempts to tax the American colonies began. But these were not thirteen identical colonies; each had a unique relationship with its mother country, as well as a culture and economy that often reflected its place within the larger mercantile system of the British Empire. Each then reacted in its own way to the British attempts at taxation. Virginia and Massachusetts, for example, became more radical. As a result, these colonies sent such representatives as Patrick Henry, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Hancock, and the two cousins Samuel and John Adams, all of whom were more inclined to support independence, to the Continental Congress. By contrast, colonies such as New York and Pennsylvania sought reconciliation over revolution and sent representatives that were less inclined toward independence. Consequently, many of their names have been lost to history. Some representatives from these colonies did become well known. John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, author of Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, challenged the right of Parliament to tax the colonies and had a reputation as a bold defender of American liberties. Nonetheless, he chose not to sign the Declaration of Independence. Beeman's strength lies in helping readers see how such a seeming [End Page 111] contradiction was possible. His focus on Dickinson's moderate perspective reveals both the varied currents of thought in the debate that led to the Declaration of Independence and the risks involved in participating. The act of signing was both a measure of patriotic brotherhood and an act of treason punishable by death and confiscation of all property. In this context, the gravity of Jefferson's last sentence becomes clear: it contained the last words signers read before pledging to one another "our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor." Jim Blackburn,JagiellonianUniversity